Claflin University Professor Among Artists at Famed IFAM

Aug 21, 2014

Growing up on a reservation along the U.S.-Canadian border, Anthony Deiter did what other young, Native men did – he began working as a tradesman.

Growing up on a reservation along the U.S.-Canadian border, Anthony Deiter did what other young, Native men did – he began working as a tradesman.

“I was an electrical technician, I was a machinist at some point in time, I worked in the Native American steel industry,” he said. “I worked building bridges and with some of my cousins on skyscrapers and all of that stuff.

“The trades, that’s a practical vocation, but I was always sketching or drawing something, and people would say, ‘You need to do something with that.’ When I was in tech school for the trades, my instructor said, ‘Deiter, you’re in the wrong field.’”

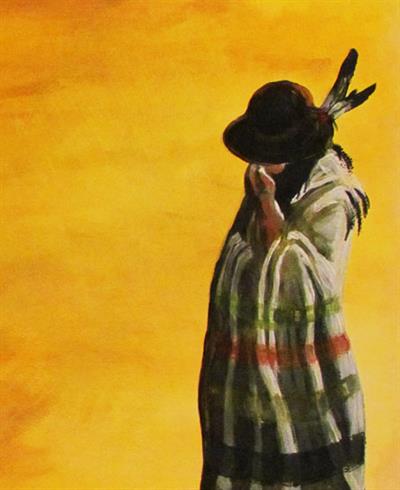

After neglecting a passion that was buried inside, Deiter decided to try his hand at using his artistic gift full-time to create paintings and digital works that tell his and his people’s stories.

Today, Deiter is a digital media arts professor and interim chair of the Art Department at Claflin University. And this weekend, he will be in Santa Fe, New Mexico, for the renowned Indigenous Fine Art Market, which highlights the crème of the crop in Native American arts.

IFAM is a celebration of Native art and the cultures that inspire it. The juried art show includes only the highest-quality artwork –paintings, beadwork, jewelry, sculpture, pottery and more – by some 400 acclaimed Native American artists. Also featured will be cultural performance stages and booths representing tribal diversity through music, dance, the spoken and written word, and more. IFAM is set for Aug. 21-23 at the Santa Fe Railyard.

“This is one of the most prestigious venues for indigenous art in North America, indeed the world,” said Deiter, of the File Hills Cree Nation in southern Saskatchewan, Canada. “I feel quite honored to have made the list.”

During IFAM, Deiter will be in the presence of such acclaimed artists as self-taught Navajo goldsmith Ric Charlie – whose one-of-a-kind jewelry can sell for as much as $20,000 apiece – and Crow Nation painter Kevin Red Star.

“This particular market has been going on for more than 100 years,” Deiter said. “There are peers of mine who make their whole living, for the whole year, on this show. Collectors come in from Japan, Germany – people collecting work from all over the world come. The population of Santa Fe doubles during this market. It’s unreal.”

“I’m going in there with no expectations,” he continued. “I’m 52, and when I was 32, I thought I’d be there, at this show. It just took that long. I’ve got lots of shows behind me, but not on the scale of this one.”

Deiter’s digital and traditional works have previously been displayed in such galleries and museums as the prestigious Grand Palais in Paris, France; the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in New York City; the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon, Canada; 2 Rivers Gallery in Minneapolis, Minnesota; the Museum of the Red River in Idabel, Oklahoma; and the Institute of American Indian Arts Museum. In 2003 and 2005, he participated as a carver in the monumental “Pou Kapua” project with Maori and indigenous artists from around the globe in Auckland, New Zealand.

His experimental animation and film work has also been shown on PBS, and Deiter was among the artists featured in “Native Views: Influences of Modern Culture on Art Train USA,” a traveling exhibit housed in vintage rail cars that went on a national tour across the United States in 2007.

“I guess my biggest show to date was Paris, because that was internationally juried,” he said. “They chose 14 artists to show, and it was at the Salon, which is one of the top galleries in the world.

“I’ve had some great experiences.”

The road to IFAM has been long, said Deiter, who joined Claflin’s Department of Art in August 2013. He has been working for more than 20 years as an aboriginal contemporary storyteller, employing sculpture, 3-D digital animation and other computer technology to communicate the story of North America’s Native people through references to his own history. He has taught at the University of Northern Kentucky, King College, the University of South Dakota, the First Nations University of Canada and the Institute of American Indian Arts.

“I was always an artist, but I didn’t take it serious,” Deiter said. “My father was actually a very gifted artist, and we grew up in a hunt – I might have caught the tail-end of where my people survived and subsisted on hunting – and so my dad was a hunter, and I hunted with him a lot when I was a kid. … If he saw a moose or a deer or an elk or something, he would draw this picture with a pencil. He would sketch it all out and explain everything.

“I was always a drawer as a kid, but where I come from, people go into the trades. I grew up on a reservation, so when you get out of school, you’re either going into the trades or you’re going to the city. Post-secondary (education) really wasn’t an option back then.”

But art was never really far from him – Deiter took summer courses and he would paint, and he discovered that it was something he enjoyed. After being encouraged to attend art school, Deiter took a shot and applied to the prestigious Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe.

“It’s the only four-year college for Native American artists in the nation. A lot of famous Native American artists have come from there,” he said. “I didn’t think I was going to get in.”

Deiter compiled a portfolio of 10 images, put the package in the mail and forgot about it.

“I was back working – at that time I was probably in construction – and this package comes about two months later. And I thought, ‘Oh, here it comes … a rejection letter,’ but it was an acceptance letter to this school,” he said. “And all of a sudden, I was like, ‘Oh, well now I have a big problem, because now I am accepted in this rather prestigious art school … how am I going to get there?’ I was on the reservation. I was in Canada at that time, I was working, and I started checking into scholarships and I got scholarships.

“The next thing you know, I was in North Dakota somewhere with a duffle bag and my big ol’ hat on, and I was going to New Mexico on a Greyhound bus,” Deiter said.

“The next thing you know, I was in North Dakota somewhere with a duffle bag and my big ol’ hat on, and I was going to New Mexico on a Greyhound bus,” Deiter said.

Art school wasn’t exactly what he expected – but not necessarily in a bad way.

“Being Native American, the first thing you’re used to doing when you get in these art classes is you start drawing and painting warriors on horseback … and animals, and whatever have you,” Deiter said. “And your instructors are very accomplished artists, and a lot of them are Native, too, and they take your paintings and they throw them in the trash. They say, ‘You already know how to do that. You’ve got to do something new.’ They want you to study the masters … and then storytelling comes in, and you just don’t do pretty pictures because you can do a pretty picture – you’re actually conveying experience.

“They say the best time to start (painting) is in your 50s because you have life experience. You have something to talk about. And I just happen to be in my 50s, so maybe that’s why things are picking up for me now.”

Deiter said that artistic purpose is clearer to him now more than ever.

“I’m the oldest surviving member of my family, and that made me really start to think about saying something,” he said. “In my family, I am the leader, you know, and when I go back home, the young guys will run and get me a chair. I’m like, ‘Come on, guys, I’m only 52,’ but as the oldest surviving male, for them, that’s a big deal. So I think that makes it very important that I start to say some things that people can take away, and it’s hopefully a positive message.”

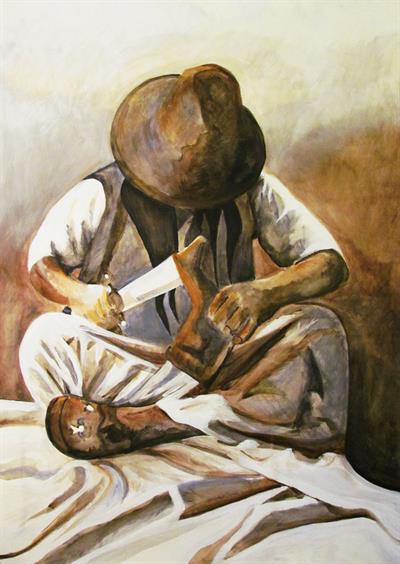

Deiter’s art focuses not only on life and stories, but on beliefs, too. While he mostly works in acrylic and oil, Deiter is currently experimenting with gold leaf and would like to work with precious metals one day.

“I’m very metaphorical in my work. I don’t literally tell you, but I will give you enough symbology that you may figure out which direction I am going,” he said. “I’m actually doing one right now based on the white horse, which is very sacred in many cultures, not just one. The Cheyenne had the white stallion, my people had the white stallion, but then you go on to belief systems and there’s always the description of the white horse. So why does this keep reappearing? I’m doing it from my perspective, but you could read it interculturally.”

After earning his Associate of Fine Arts degree in 2-D from the Institute of American Indian Arts, Deiter went on to earn his BFA in sculpture from Arizona State University and his MFA in 3-D from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“While I was at Wisconsin, as a sculpture major, this mentor that I was assigned to, (emeritus professor of art) George Cramer … kept badgering me about this one elective called 3-D animation, which was a brand-new program in the 1990s in Wisconsin,” Deiter said. “I kept turning him down, saying, ‘I’m a sculptor – what do I need to take 3-D animation for? Why would I even do this?’ And he said, ‘What’s it going to hurt to take an elective? Try it out, see if you like it.’ They were actively going after sculptors for 3-D animation.

“He talked me into it, I took it, and I realized right away why they were seeking sculptors … Sculptors see in the round – think about ‘Ice Age’ or ‘Toy Story,’ that’s 3-dimensional … and they need people to be able to create that. Sculptors think in the 3-D.”

To do 3-D animation, Deiter said you first have to be an artist.

“The computer scientists are the ones that make the whole thing go, but sculptors are the ones who create the environments and the motion,” he said. “There were a lot of opportunities in that field at that time, and there still are. It’s quite a big field.”

After graduating from UW-Madison, Deiter had his first animation show at the Smithsonian.

“I got known for my digital work, but as I was moving along, I kept missing the studio,” he said. So the last few years have been a return to his roots – drawing and painting.

“Now, I’m doing a little of everything,” he said. “It’s totally a creative field, no matter which way, and in the Art Department, I can be teaching a computer animation class and a painting class in the same day, and getting ready for shows and then getting students ready for that, so it’s a very creative environment.

“You’re multitasking. I’m doing four canvases, four different stories, right now, and actually, I think I’m shortchanging myself – I should be working on six or seven.”

Art is a gift, Deiter said – “You are either gifted with it or you are not” – and those who are blessed with the gift are instrumental to society.

“Without art, there wouldn’t be a lot of our physical world. The computer you’re looking at? An artist conceptualized that design. That car you’re driving? An artist conceptualized how that was going to be shaped. That desk you’re sitting at? Again, everything you interface with in the world is done by an artist at some point in time,” Deiter said. “Things just didn’t arrive at these shapes by happenstance. Artists conceptualize a design, and then you marry that with technology or engineering or whatever to arrive at a product. People don’t tend to think of that.

“What you see on television, the special effects in movies, the posters on your wall, your earrings, the design of your shirt, your shoes – it’s all art.”

“I tell my students that you shouldn’t be in the field to be famous, because that ruins the whole thing,” he continued. “Appreciate that you’re a storyteller, and don’t think nobody wants to hear your story because they don’t know your story.”

For more information about Deiter and his work, visit his portfolio website at www.kamajes.com. For more information about IFAM, visit www.indigefam.org.